Unexpected Applications of Lund’s Early Retirement Extreme

Manuel Tarrazo1

orcid.org/0000-0003-0301-8751 Abstract This study examines Jacob Lund Fisker’s book Early Retirement Extreme. The author’s recommendation rest on two pillars: one philosophical, inspired by Renaissance-like education and living, and the other computational, a non-traditional approach to financial planning. I clarify his computational approach and show its relationship to traditional approaches. For example, Lund’s method to provide years of coverage for alternative, not necessarily salaried living is forward looking. He starts by determining the amount of savings possible in each year, and the number of savings years needed to finance a given period ahead of a different working (or non-working) arrangement. His approach stresses savings (accumulated during the regular working years and after) and downplays interest rates. I show that Lund’s framework provides valuable insights not only on retiring early, before the legal age to draw funds from Social Security, but also for general retirement planning and many other practical situations in which there is little time to prepare for retirement. JEL Classification: J26, J32 Keywords: Retirement Planning, Early Retirement, Time-Value of Money 1 Professor of Finance, School of Management, University of San Francisco, 2130 Fulton St., San Francisco, CA 94117-1045, USA.

Corresponding Author: Manuel Tarrazo, PhD, Professor of Finance, University of San Francisco, USA. Email: tarrazom@usfca.edu. I. Introduction What I describe here is another kind of life, the life of an independent wealthy and widely skilled person –a modern Renaissance man. Lund Fisker (2010, p. ix). Nowadays a simple mode of life is difficult: it requires much more reflection and inventive talent than is possessed even by very clever people. The most honest of them will perhaps say moreover: “I haven’t sufficient time to reflect on it. The simple mode of life is too noble a goal for me, I shall wait until wiser men than I have discovered it.” Nietzsche (1996, p. 359). A few years ago, as part of routine learning and preparation of my lectures, I bought Jacob Lund Fisker’s Early Retirement Income: A Philosophical and Practical Guide to Financial Independence (2010). As part of the finance faculty, I have taught the usual corporate finance/financial management and investments courses. At the time of my purchase, I was doing preliminary work on establishing a personal finance track in our major in the School of Management, perhaps linked to specifics professional designations (e.g., Certified Financial Planner, Chartered Financial Counselor). Other colleagues in my department carried out similar work concerning tracks for specialized risk-management, and a master’s program linked to the Chartered Financial Analyst designation. The third option won, but the work done to evaluate the personal finance option was not wasted in any way. My research was strengthened, the household financial planning perspective with which I complement my institutional one also improved, and my selection of a problem to work on benefited from my enhanced exposure to the financial and nonfinancial challenges faced by households. Lund’s (2010) book came with an eclectic group of other purchases, including (in no particular order)

Lund’s (2019) book was different from all of them, but the personal finance nature of his contribution makes the work relate, in some way, to all the others on the list. I found myself thinking that the book had solid and specific content, but was it teachable? Could the book be used as complementary reading in a personal finance or investments class? It was not a textbook, but could it be that it was more than a textbook? A few years after my purchase, and after having one copy of the book at home, and another at my office, I started to write these few pages to facilitate learning from this uncommon source. The first challenge was how to handle the “Philosophical” part in the “Guide for Financial Independence,” as philosophy is something rarely associated with any research on household financial planning. Lund’s philosophy and philosophical approach appear as the intangible center from which his writing originates, infusing his practical plans with powerful rationales and lending credibility and expectations of favorable outcomes to his decisions. There can be no doubt about the role played by the great “whatever” that seems to generate our life behavior and actions; call it philosophy (or lack thereof), or education (or lack thereof), or practical learning and experience (or lack thereof). Once that great whatever is dodged, our efforts to learn, explain, and improve our financial and economic behaviors seem to become of lower, but still of not at all unimportant, concern. Without that intangible whatever, we may feel we are only juggling a few constructions (life-cycle theory), formulas (the time-value of money), some hypotheses (e.g., interpersonal comparisons of utility), and reflections (the society of consumption, sustainability). In the end, that collection of disparate things becomes all we have to best employ economics and finance to improve our lives and those of our dependents. In order to fully appreciate Lund’s contributions, I will include the tangible and intangible elements in in his early retirement approach. A critical issue is how much and how well theoretical constructions (math formulae and qualitative and quantitative models and setups) help us to implement, if not desired, at least satisfactory, economic behaviors leading to meeting specific, not necessarily quantifiable life targets. Part of Lund’s writing strategy is to follow the structure of the hero’s path: 1) initiation—the call; 2) the descent into the abyss; 3) return with the goods of enlightenment, and 4) enhanced experience of living. The organization of this note is arranged to respect Lund’s flow of thought and to allow sufficient room to examine the financial planning implications of his approach to early retirement. Therefore, I found it useful to arrange the note into three parts; the first one focuses on mostly qualitative issues (the first three steps in the hero’s path); the second focuses on mostly quantitative elements (tools, formulas, plans); and the third examines the practical value of the previous materials in the context of alternative approaches. Very curiously, a first reading of the book proved to be intellectually stimulating on the overall treatment of the retirement problem and its handling of the required quantitative apparatus, both of which eclipsed thoughts of practical applications. Then, a few related newspaper readings revealed quite sharply the practical value of Lund’s approach, albeit in perhaps a different way than the author originally intended. I close this note with concluding comments and references. II. Initiation, Reflection, Enlightened Return These concepts are covered in the first four chapters of the book. Lund’s development of his approach to retirement planning begins with a vital, philosophical quest. In fact, it resembles a modern hero’s quest, as presented by Joseph Campbell – the call and departure; the road of trials and initiation; and the final return and freedom to live – (originally published in 1949). But it is perhaps best captured by those initiation rituals of olden times, whose parts and purposes we can extract from pieces such as Virgil’s Aeneid or accounts of the travails of Odysseus/Ulysses, Orpheus, and others. The canonical steps of such quests are these: 1) initiation, reflection, ill-being; 2) descent into the infernos (catabasis); 3) return with wisdom (anabasis), and 4) enhanced and higher living. In addition, Lund’s quest includes a plan and practical guidance for achieving independent, enhanced living full of purpose through household financial planning. I cover Lund’s work as follows: 1) Initiation and reflection – the call: Chapter 1, “A different frame of mind” 2) Descent in search of understanding: Chapters 2, “The lock-in” 3) The enlightened return, the going up, the coming back: Chapters 3 and 4, “Economic degrees of freedom” and “The renaissance ideal” 4) The plans and practical foundations: Chapter 5 “Strategy, tactics, and guiding principles” Chapter 7 “Foundations of economics and finance” 5) Enhanced and higher living: Chapter 6 “A renaissance life-style” Initiation and Reflection – The Call The call, a lofty term leading into some very special household financial planning, happened during the author’s formative years. He recalls how he learned many things, from arithmetic to punctuation, and then physics and geology, “Yet, I never learned why the world worked the way it did” (Lund, 2010, p. 1). The questions intensified when he was working as a research assistant in physics and faced doing what other people do at that age – saving for retirement, buying a house, getting married, buying a car, buying certain types of clothing, and preferring some beverages to others “if it came from a certain kind of bottle.” He also entertains other rather uncommon questions: “Why do we use money instead of promises or favors?” “Why do we live in houses and not boats or cars?” “Why are there usually 2-4 people in a home and not 10-20?” “Why do we move away from home?” The type of work he was doing provides hints about his unusual quant resources and what he was trying to get to. But, at this point in the book, he has not provided any further clues to his education. He makes those revelations in the Epilogue, right at the very end of the book. I get back to this when I evaluate his financial planning formulas. In his next paragraph, Lund is in Plato’s cave, in the company of other prisoners, able to see only shadows in the cave/prison wall. Lund describes what would happen when a prisoner was released and then came back to the cell. He sees the pitiful state of his former mates, seeing shadows, loaded with chains, some still content in their ignorance. He tries to tell them, but “they do not believe him – and why should they? … Taking off the chains requires too much effort, so most of them remain seated. These are people who are very good and successful at identifying, naming, and dealing with shadows, and so they may not want to leave” (p. 2). Lund then immediately jumps to the present time, “In real life, the prisoners of Plato’s Cave are those who are prisoners or slaves to their wages and their culture. A wage slave is a wage earner who is entirely dependent on their wages; He is still entirely focused on the wall. The wall shows other people not as who they are, but as what they own… A wage slave is a person who is not only economically bound by mortgages, loans, and other obligations. But also mentally bound by an inability to perceive that there are other options available, like the prisoners in Plato’s Cave... The chains are mental ... too win the “prison game,” which means accumulating at least a million to retire? $1 million now is considered insufficient by a growing number of people, even though most people will never accumulate such a sum” (p. 3). As the reader may have already anticipated, this train of thought brings to mind the criticisms of alternative living movements coming from very different angles, such as countercultural movements (e.g., community-living hippies from the sixties), ideologies (Marxist-communists idea of capitalism-induced consumption to further exploit the masses), and a variety of critiques of materialism such as Veblen and especially society’s “affluenza” – a state of affairs in which people work too much and have little time for themselves or for others, all to maintain a lifestyle where possessions diminish the value of possessions (see Schor. 1999, 1993; De Graf, 2005; Kasser, 2003; and Frank, 2000). And, yes, Lund seemingly plays this tune, “Perhaps one reason for this complacency is the large quantity of material goods available to the chain gang. Material goods are often used as compensation. Frequently, when someone is depressed, the advice is “Go out and spend some money. Buy yourself something nice. Treat yourself. Try a little retail therapy… Is spending the most productive years of your life chained to the job market to collect a lot of rarely used stuff that gathers dust in the closet or takes up space in junkyards a wise choice? Were you really born just to die, leaving a large pile of discarded consumer goods? But perhaps conformity is not the only way to live. In fact, by taking the other end of the bargain, saving as much as other people are spending on wants, it’s possible to retire and have on invested savings after just five years of full-time work” (pp. 4-5). Please breathe deeply, dear reader, there is more: “However, it’s possible to have on a third or even a quarter of the median income, putting one solidly below the government defined poverty line, without living in austerity or eating grits. It requires a somewhat different approach, though, and it requires some skill. It also requires a reprogramming of “the way we’ve always done it,” or, rather, the way we usually do it. Perhaps the best advice to overcoming this consumerist tendency to “buy, buy, buy!” is to study alternative sources of information. Ignore most of the personal finance books out there. They only explain how to play the game by the rules. Instead, use the rules to play a different game. To successfully break free of ones chains, one must build an overarching philosophy of what it means to live” (p. 7). At this point, Lund joins many religious and initiation schools and groups in establishing that the way and the rewards are not material. However, contrary to these schools and groups, Lund focuses shortly afterwards on the very mundane but also necessary realm of taking care of our homes (oikos-nomos, economics). First, he wants reader to ask themselves two questions: Is this for me? What are the barriers to changing things? The major obstacles, in his view, are protecting the ego, avoiding a change of perceptions, and underestimating the benefits of change. Willingness to initiate change may depend on a) the level of dissatisfaction with the present situation, the ability to envision a future situation, and (basically) the existence of a plan. Curiously, some of Lund’s reflections resonate the influencing events (e.g., loss of a job) and processes some entrepreneurs go through before starting a business, which is another way to become financially independent. Descent in Search of Understanding Chapter 2 is entitled “The lock-in.” Without ever mincing words, Lund reviews some of the many ways we waste time and resources (manicured nails, manicured lawns). Then we, go “create problems, spend the next day solving them, and then claim we have made progress” (p. 17). We resemble puppets being played by ill-behaved puppeteers. He goes over the following areas of interest: 1) Education, college degrees; 2) Careers: a) specialization, b) job competition; 3) The pursuit of stuff, status, and happiness; 4) Problems with personal finance: a) mortgages, car-loans, and consumer debt and b) savings and investments; and 5) Retirement as a relatively new social concept. Some matters to highlight, within the objectives of this note, are the repetitive stimuli to conform, fit in, and repeat that individuals received in their formative years. It is also interesting that one of the tools that helps professional progress, specialization, might make it harder for people to take care of a variety of necessary matters, which, in turn, creates excessive dependency on others. Some personal finance problems are the result of profound misunderstandings of debt and of what saving and investing should be. Finally, Lund believes that because retirement is a relatively new social institution, we are all still finding out about it. The all-nothing divide between either putting all our time into working or not putting any time into it seems too drastic In the last section, entitled “Breaking Out,” Lund spells out some key specifics, which become the three (qualitative) pillars of his approach to early retirement:

The following two chapters try to demonstrate that there is a way to implement these mostly qualitative reflections, which are consequent with having established that the ultimate reward is not necessarily related to material rewards. The Enlightened Return In the first chapter, Lund observed that one obstacle to change for many people is the lack of a vision of the present (they are in a cave) and of the future. Chapters 3 and 4 presents some materials and reflections to construct helpful and productive visions and more. They represent the enlightened return of the hero, the going up, the coming back. First, coming to terms with what is in the present (Chapter 3), Lund proposes classifying people into four different types:

Lund next explains what the classification means. In part, it is to highlight that specialization has some attractive aspects (e.g., steady income) but also limitations and drawbacks such as dependency, lack of self-confidence, and a narrow field for self-realization. In this context, one can say that the so-called primitive man was not devoid of general purpose “human capital,” which is a very modern concept. There are some comments on systems couplings, how different types must fit in different mold, and capacity to change “species,” ergodicity and destiny (i.e., predetermination). Like many ancient civilizations, Lund also highlights the importance of self-confidence of having tried oneself, the ability to become independent: “Doing something that is considered very difficult at least one in your life is highly recommended” (p. 57). The subsequent three pages reflect on history, culture, and change. He thinks our present cultural model is not going to last. Just as Renaissance thinking was ideally suited to overcome the Dark Ages, a modern characterization of the Renaissance ideal – polymath, self-confidence, self-sufficiency – appears as a solid way to manage whatever may come. (Technically, the Renaissance did not follow the dark ages, the roughly five centuries following the fall of Rome; but there is no problem in his argument, especially considering that the Renaissance overcame the Black Death, which took nearly one third of the population in Europe. It also partially co-existed with a rather nasty cooling period called the Little Ice Age.) Chapter 4 is dedicated in full to the Renaissance ideal. “A Renaissance man excels in a wide range of objects” (p. 61). This, the opening sentence in the chapter, seems to refer to some sort of unusual Leonardo Da Vinci, but the idea is far more reasonable and temperate: “Don’t worry about whether you can eventually become an expert. Rather, try to constantly improve on the subjects you already know and seek our useful things to learn” (p. 61). Lund writes, “With a process-oriented attitude you’ll eventually master several subjects. Once a threshold is reached, the synergy between different subjects will help you create new solutions. Since all human knowledge is based on a limited number of mental models, the stronger and wider this foundation of models is, the easier it is to gain models” (p. 61). Here, Lund touches on something interesting. There is something positive to be said about espousing a Jack-of-all-trades attitude, not only in terms of enjoying self-sufficiency but also in term of simply getting pleasure from learning. He then suggests that primitive people were better served by their general knowledge than modern men, who are more specialized but less self-sufficient. Instead of the specialization strategy, which produces only one source of supporting earnings, he favors using different areas of less-than-expert knowledge to accumulate self-supporting cash flows. He recommends the following areas of knowledge: physiological (health), intellectual, economic, emotional, social, technical, and ecological. He again notes, “[T]he universal ideal does not require total mastery of a subject; it only aspires to it” (p. 65). The Jack-of-all-trades comes back to mind – a person who learns foreign languages, self-instruct playing musical instruments, and puts some time into drawing or different forms of painting (watercolor, oils, etc.) is likely to be pursuing those activities not to become a master of everything but for the pleasure of trying and cracking the learning process. This joy of trying different things is obliterated by the impression that we are only supposed to exist and count in what is called our “area of expertise.” The last segment of this chapter emphasizes that the most productive type of education is one of a general nature. At this point, even a sympathetic reader may feel some impatience. It may help to keep in mind that this chapter’s objective was to outline an ideal – the Renaissance ideal – as it might lead to independent living, including its financial aspects. Specifics concerning the required lifestyle are covered in Chapter 6, “Renaissance Lifestyle.” The next chapters also cover financial planning and financial tools. It is also helpful to briefly look back to what transpired in this first part of the journey. It all started with a Socratic call – the unexamined life is not worth living. The author’s examination followed Plato’s cave allegory and led him to some of the jewels of Roman philosophy, always considered “the practical” one when compared to that from Greece: Epicureanism, select what you get, and stoicism, make the best of anything you go through. Then, there was a reflection on the many troubles we manufacture for ourselves, as if listening to Bishop Berkeley – we raise dust and we company we cannot see. And what about our professional life and wondrous careers? Doesn’t it make us feel like, as Samuel Butler noted, “We are like billiard balls in a game played by unskillful players, continually being nearly sent into a pocket, but hardly ever getting right into one, except by a fluke”? Yes. Yes, to all, but Lund is justified in repeating on the bases, “Everything has been said before, but since nobody listens we have to keep going back and begin all over again” (André Gide, Le Traité du Narcisse). At this precise moment, one may feel like reading Walt Whitman’s “Song of The Open Road” one more time, which is also about gaining independence of mind and immersing ourselves and enjoying the fullness of living. I want to get into the math. III. Plans, the Math, Rewards, and Obstacles The second part of the book focuses on implementing in practice the ideas and principles set out up to this point. There are qualitative matters and quantitative ones. We will cover the last chapters of the book slightly out of sequence, as indicated below:

Strategy, Tactics, and Guiding Principles The contents and objectives of Chapter 5, “Strategy, tactics, and guiding principles,” are hard to understand. The terminology concerning strategy, the development of expertise, and certain steps (e.g., compiling, computing, and coordinating) is not easy to place in the financial or retirement planning literature. Presumably, whatever the terms, what is dealt with in this chapter leads to putting together a plan. His terminology seems to have originated in information theory, and he introduces the concept of complexity and degrees of freedom next. However, this terminology is not retirement-planning-client friendly, and the material that follows on strategic principles, modular design, homotelic and heterotelic responses, effect-mapping, webs of goals, and tensegrity seems unnecessary and distracting. At some point, we read in a boxed text, “A good strategy solves multiple problems at the same time!” (p. 92), and we welcome it as it means a return to good weather, but not too long afterwards, we also read that “there are no such things as needs and wants” (p. 98), which was a bad decision on the authors’ part. The difference between needs and wants is one of the most useful constructs in our society. It is easy to state: a need is something that you have to have; a want is something you would like to have but may not need. It is staple in marketing courses. And it is critical for retirement planning because it allows a differentiation between really necessary items and not-essential (discretionary ones) ones. Then, we are able to clarify budgets and investments. We can, for example, “dedicate” certain financial resources to cover those necessary items, see Huxley and Burns (2005). It turns out that what the author has discussed in the first part, seeking enlightenment, and living an independent life can easily be understood by differentiating between needs and wants. His own discussions in some of the following sections seem to use the standard needs vs. wants categories, “Since humans need very little, eliminating various wants can go far in terms of solving problems…Reduce and simplify! Reduce and simplify!” (p. 103). The material that follows focuses on building blocks, construction methods, appropriate responses, sigmoid, logistic curves, and the maximum power principle. The last concept can be put into very simple terms: overdoing anything reduces its value. Lund’s mention of certain characteristics of exponential functions, which are taken at face value in both the theory and practice of financial planning, is noteworthy. These functions (and their logarithmic cousins) provide both powerful ways to plan and useful shortcuts (half-life point, rule of 72, and so on), but blind use has its dangers as well. For example, we get the same future value when investing a given amount of funds, say $100, for 10 years at 4%, or for four years at 10%. Their product is the same (0.04 * 10 = 4 * 0.1 = 0.4), and that is what counts in the formula being used (fv = $100 * e ^ (i * t ) = $149.18). However, in reality, we would be rather concerned about the added risk in expecting 10% rather than 4% or in having to wait 10 instead of four years. Exponential functions are used in physics because they match certain processes (e.g., radioactive decay); finance is a different matter, and we use them in financial planning because we do not have anything better. In retirement planning, careless swapping of values between interest and time may create a dangerous illusion of feasibility. Chapter 6, “A Renaissance lifestyle” kicks in at this point. It begins with some practical guidelines and then goes over a) “things”: things to own and how to avoid getting them, how to get rid of them, how to get them, and how to make them; b) shelter (living, eating, hygiene, living with others, rent or own decision, how to find shelter, telecommuting); c) domestic food supply; d) lights and electric, heating and cooling; d) clothes: how to build a wardrobe, laundry; e) health; f) transportation; g) services; and h) people: spouses and significant others, children. In its present form, Chapter 6 creates a discontinuity in flow and purpose, and it might discourage even the most sympathetic readers for at least two reasons. First, the book is likely to have been bought because it explicitly attracts attention to early retirement, and, as elaborated in the introduction, to the strategy of working intensely for some years, while resetting lifestyles and habits, to minimize work, maximize independence, and set up a self-sustaining system for the rest of the years. Then, where are the specific steps? Second, the book is about 90% finished and we still do not know what to do. How do we know how are we doing, how much we would need to change? And, most importantly, how much of a change would we have to impose on others? What the book needs before the chapter 6 is the math, which, in the current organization, seems to appear as an afterthought, rather than as a critical component. The Math Although the placement and length of the section on math make it feel like an afterthought, Chapter 7, “Foundations of economics and finance,” could represent the jewel of the crown in the book. Lund first illustrates what financial assets are best for making your money work for you instead of you working for it. He focuses on cash flows and shows how debt and “stuff” (buying things) can sabotage the goal of having your money work for you. He considers the possibility of multiple work revenues and presents an interesting cash flows diagram, accompanied by this commentary, “More important, though, is the primary reason that so many complain that they are not “getting ahead,” which is apparent from the figure. It is the loss of wage to waste and other people. This constitutes a lot of hard work for nothing, and it’s the reason why so many, after decades of work, have so little to show for it” (p. 189). After building some asset base, it is other people’s money that flows to the person: “A worker acquires assets by consuming less than his income and then saving and investing the rest” (p. 190). One of Lund’s major contributions comes in here: figuring out how many years’ worth of retirement can be finance with a current year of work, given a certain level of expenses. For example, if a person earns $100,000 dollar in a year and spends $50,000, s/he will need to work two years to finance one year away from work. In other words, at that rate of saving (50%), each year finances half a year of retirement. Lund then adds investment returns; the $50,000 saved each year would be invested and would earn a given rate or return, which would add some extra-retirement time. Another major contribution follows: Lund does not look at the extra money when accumulating/expending money but at the extra time gained/lost. Lund algebraically deduces the number of periods for the case of discounting an annuity due to show that the main drivers in the process are the number of years worked and the saving rate (50% = $50,000/$100,000) in the previous example. The implications of proceeding this way are very important:

Traditional retirement planning follows this setup: Step 1. Distribution stage. Work backwards; start with the years during retirement – the distribution stage. Set a desired level of consumption for the retirement years (pmtr), then set the number of periods (years) being considered during retirement (tr, retirement time) and write down the rate of return on investments during the retirement period (rr, return during retirement). Given these inputs, it is very easy to calculate the funds needed (pvr) at the beginning of retirement. Step 2. Accumulation stage. Write down the figure produced in the previous step; it shows the target funds for the accumulation effort. How much do we need to set aside each year to reach that accumulation goal? In order to answer, we need the number of years until retirement (ta, time away from retirement) and the rate of return earned on the investments (ra), and we already have the funds needed – the future value during accumulation, fva, which equals the present value at the beginning of retirement = pvr). Again, it is very easy to calculate the money to be set aside for retirement (pmta). This model is not bad at all, but it has some potential issues. During the distribution stage, the length of retirement is not discussed, perhaps beyond some life-expectancy considerations. The way the costs are set during retirement is not conducive to much scrutiny or evaluation either. And the rate of return during retirement comes out of nowhere, as if it was a star in the nightly heavens. During the accumulation stage, lifestyle is never questioned; therefore, its effects on retirement are much downplayed. Somehow, the time, rate of return, and size of retirement savings will contribute to reaching the target. Closeness to disaster (low savings, low rates, not enough time) is somehow discounted by assuming conservative estimates in each variable. What dominates the planning exercise is the coherence of the method, not the behavior of the planner or changes in the planning environment. In the end, without questioning the model structure, lifestyles, or time-lengths, the hopes are likely to be pinned down in the rates of return. Lund’s framework is very different – one cannot fool oneself or others. Each year without working while still spending requires either saving that much every working year or working that many more years. No hopes pinned on magical finance rates. They will not save the day when one does not have the money and the time. As we approach retirement with weak positions, saving rates have much more effect on accumulation than rates of return. (Lund does not discus Social Security because he is focusing on supporting himself prior to the legal age required to draw social security. His analysis, however, is useful for general retirement planning as well.) Chapter 7 is not easy to follow even for someone with a substantial understanding of what is called the mathematics of the time-value of money. All his formula-driven numbers are contained in six pages. In addition, his approach differs from the traditional approach described earlier, which requires readers to constantly exert themselves to map the material to more familiar systems. Lund should have started at the very beginning of the problem to be solved. First, how much money can I accumulate in my situation? And second, how long will the money last? Let’s address the first question. If one invests an amount p (payment, PMT) each year, earning an investment rate i during T years, it will accumulate to a fund P0 of a certain size. There is a readily available formula expressing this: P0 = future value (FV) = payment * ACF (1) where compound factor (CF) = (1 + i)T, and annuity compound factor (ACF) = (CF - 1)/i.

Given a fund P0 of a certain size, earning a rate i, and planned draws (PMT) each period, how long would the funds last? Again, there is a ready formula to answer that question: P0 = present value (PV) = payment * ACF (2) where, discount factor (DF) = (1+i)-T and annuity compound factor (ADF) = (1-DF)/i. This is Lund’s formula 7.9 on page 100. My formula looks different from his because he assumes that payments occur at the beginning of the period (annuity due), rather than at the end or the period (ordinary annuity) as I do to emphasize clarity.

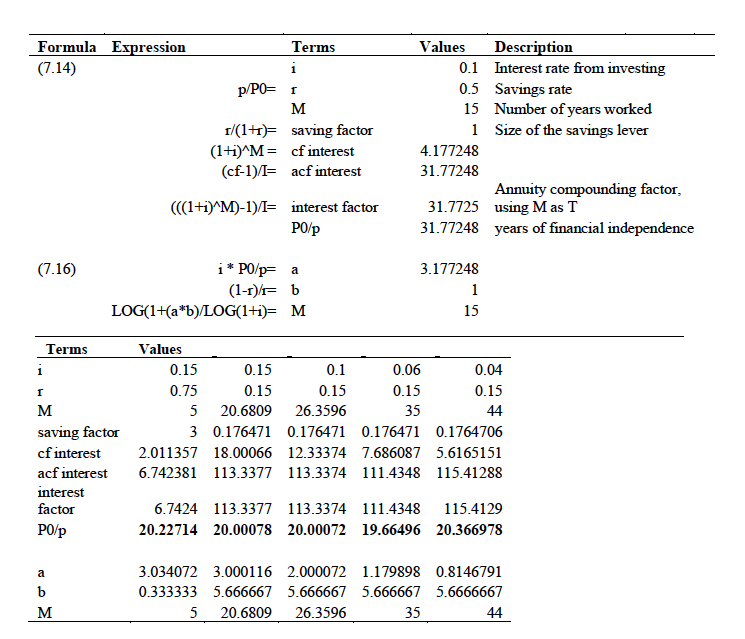

Next, Lund expresses the formulas above as FV/PMT = Po/p = ACF(i, M) (3) and PV/PMT = P0/p = ADF (i, m) (4) He does this for two reasons; first, to separate the numbers related to amounts accumulated – say, the amount of water in a bathtub, to be accumulated (FV), or already accumulated (PV) – from the money flowing into the bathtub (i), or flowing (draining, leaking) out of it (p, PMT). In a way, planning for retirement is rather similar to preparing a warm and relaxing bath. We must open the hot water faucet, let it run for a given amount of time that depends on the rate of flow, then enjoy the bath. The second reason to express the formulas as done in (3) and (4) is to observe than controlling the ratio size/pmt (the savings lever when accumulating, expense ratio when using funds), is far more powerful than relying on the interest rate (i) or banking on the time. Lund’s framework also shows that mastering the retirement problem can be regarded as a matter of managing the time variable. Lund’s formulas 7.10 (p. 200) and 7.15 (p. 202) provide the lengths of time to accumulate (TA) and deplete funds (TD), respectively. They can be employed to find out how much to save to accumulate the necessary amount in the shortest amount of time (TA), and to provide financial independence during the retirement period (TD). In addition, Lund does not use T for time, as it is customary. He uses M, the number of years worked. This is very insightful because it emphasizes that each year of work is actually an investment of size p. Exhibit I presents a brief example of Lund’s retirement math. The tops shows an example with a return on investing of 10% (i = .1); a saving rate (r) of 50%, which may correspond to many different savings-to-earning values (50/100, $50,000/$100,00, and so on); and 15 as the number of years worked (M = 15). The solution is 31.78 years of financial independence, during which, presumably, the person will maintain the current consumption levels (same i assumed). The bottom block presents different scenarios for changing investment returns (i), savings (r = p/P0), and number of years worked (M). As Lund explains, the same number of years of financial independence (P0/p; from the text, we gather he means about 20 years, though he never states that explicitly) can be obtained in very different ways, a short period of five years would need ruthless savings and very modest retirement expenses; while low investment returns and living it up (small saving from earnings before retirement and large expenses while retired) can only accomplished by working during many years – the usual suspects’ case. (It is fair to note that Lund’s explanation is very hard to follow. He does not give single, explicit numerical examples like those in Exhibit I. Instead, he presents multivariable graphics that have to be pieced based on the implications in the author’s text.) This is the moment when readers might welcome having the materials in Chapter 6 “A renaissance life-style.” It is now the time to reveal what could have been spoilers. The author is very well educated – a doctorate in nuclear physics, the field in which he work for only about five years before his extreme early retirement. He is also well read. He maintains a website with additional guidance to implement his approach (http://earlyretirementextreme.com/about) and expresses his success in this way: “Current net worth (2018): 129 years’ worth of annual expenses.” Exhibit 1: Lund’s math IVSource: Author’s work.

Preliminary Critique It is appropriate to provide a critique–which will be preliminary, because there is still another section dedicated to a more comprehensive evaluation, and brief, because it is best to let readers think over their own reactions. Taking Lund’s text at face value probably means viewing the book as offering a way to work intensively for a few years to finance a decent retirement for many years. In order to do so, it seems he recommends not only Spartan but also intelligent household management. My concerns at this point are the following: · Significant other(s). One needs luck to fine tune lifestyle and day-to-day living to be able to implement “special,” non-standard plans. · Dependents. Children and elderly in need of help come with what they come with, and even spending the minimum/optimal amounts may be difficult, not to speak of unexpected matters. · Government and society. We are immersed, neck deep in a river of expectations, to-do’s, and need-to’s that impose on us, even when we think we have become “wise to the game.” Not only are there established practices we may not be able to do much about (title insurance, costs related to transportation, fees, etc.) but we are trapped by the government and its operations, which ends up taking a very large share of our revenues and investment returns and even taxes whatever is left over when we die. The 20%, 30%, 40%, or even higher, taxation burdens that feast on professionals and professional couples are a major cause of household planning stress. At some point, we might feel we have to make as much money as possible simply to prevent the tax impact from disabling our present and future plans. An older draft of this study ended at this point. And the manuscript rested on its folder for a while. It seemed it was probably going to be hidden for as long as Tolkien’s ring, but something happened that made this material very, very hot. IV. Uncovering the Core Strengths in Lund’s Early Retirement Planning As noted earlier, the material gathered by my close reading of Lund’s Early Extreme Retirement looked promising despite apparent objections – too philosophical and general, the math seemed insufficient to properly address the problem stated, and others noted in my preliminary critique. Something else seemed to be needed to make the narrative worth its while. These three pieces appeared in the popular press like a meteor shower and clarified the missing element needed to properly value Lund’s contribution:

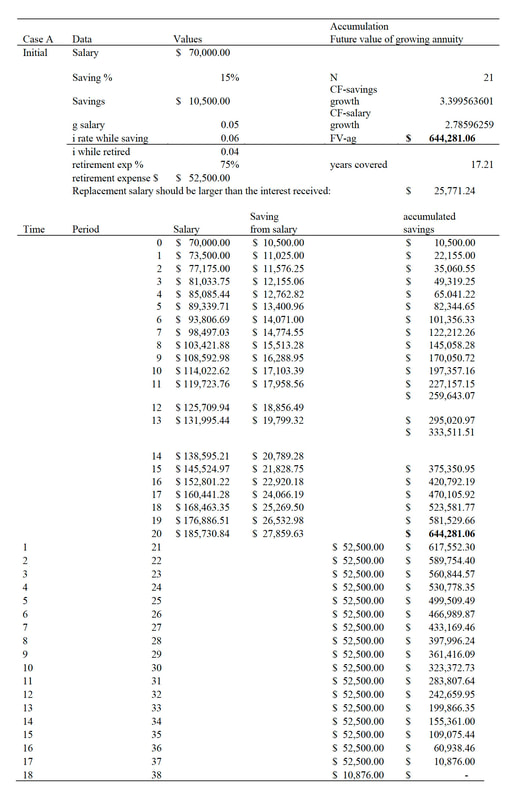

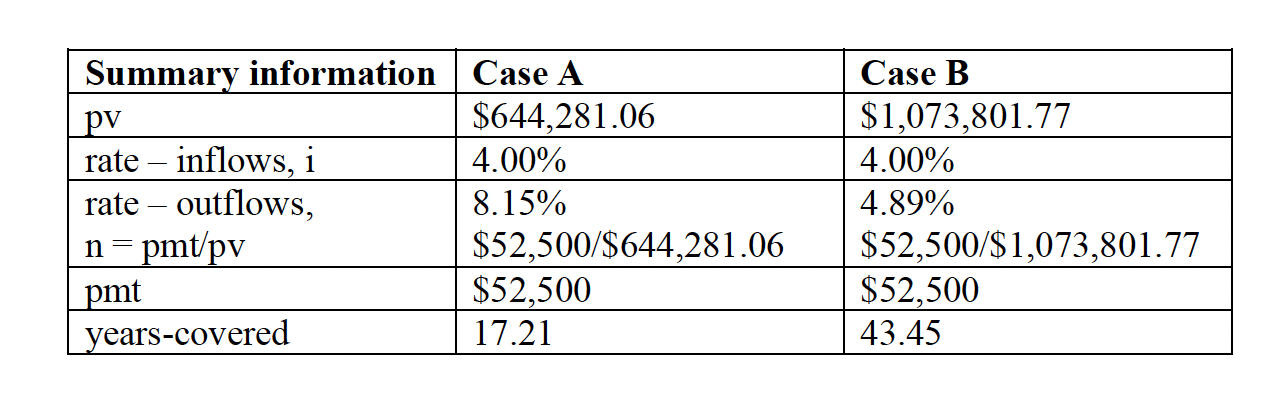

What these articles address, along with many others increasingly hitting the same notes, is the worry about retirement planning in the context of apprehension about a) what may come, b) not having enough saved, and c) feeling that it might be already too late. It is in this context that Lund’s approach can find its best, most immediate application. I start by reviewing the main insights in Lund’s approach: 1) Focus on time, and specifically the number of working years and the number of retirement years to cover. 2) Manage consumption above all, which provides the two most powerful levers – maximum savings before retirement, and minimal expenses during retirement. This approach presents the situation in its starkest form, focuses on those factors with the highest effects on plans, and right-sizes expectations on financial returns, which are totally irrelevant when the amounts invested are small and they have no time to grow. As suitable as Lund’s approach might be, his math is still insufficient to address these practical cases that include catching-up and must consider what might happen in terms of investment rates during a likely longish retirement. Lund’s analysis looks more like a one-time momentous change, and his investment rate of accumulation is also used during retirement in the formulas presented. These limitations can be addressed by 1) showing the process of growing an annuity to represent the catching up, while showing what the retirement landscape might look like, and 2) adding a retirement management segment built upon the working/investing years. Both segments share the same expense budget and highlight major, absolute dollars values and time effects, without which I can do very little. Note that the process is forward-looking, unlike the traditional model, which is set backwardly. Exhibits II and III show my extended model in action. Cases A and B only differ in the percentage of salary saved and invested. Case A shows a household/individual earning $70,000, which will grow at a 5% rate during the period considered (20 years). Saving 15% of earnings and earning a 6% return, the funds accumulate to $644,281.06. These funds are then dedicated to supporting the person/household during retirement, at a rate of $52,500.00 per year. This is 75% of the $75,000 dollars, but about 28% of the last yearly salary earned ($185,730.83). During retirement, the funds are invested and earn 4%. In this case, the saved funds only cover 17 years of retirement. Exhibit 2: Extended retirement model: Case A Source: Author’s work.

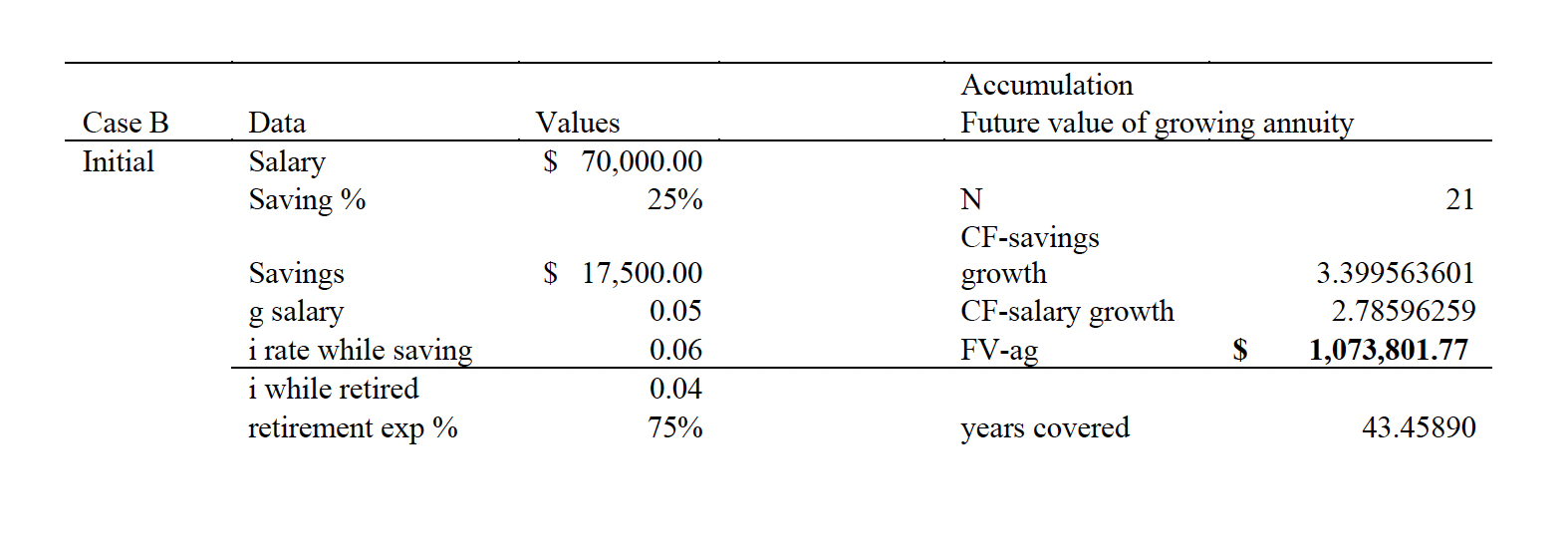

Exhibit 2: Extended retirement model: Case B Source: Author’s work.

In contrast, the household/individual in Case B saves 25% of salary earnings, which accumulate to $1,073,801.77. These funds will cover 43 years of retirement, thanks to the power of the consumption-saving lever. Note: In Exhibit II, 15 rows have been hidden, between the 10th and 25th years, rows boldfaced, to be able to keep the table to one page. The top right-hand side in each table shows two formulas that provide 1) the terminal value of the growing annuity and 2) the number of yeas the accumulated amount will last. The calculations should be performed both in extensive form and with formulas (closed-form: the formulas are not at all as complicated as they might have looked at first sight. For example, this is the expression for the terminal value of a growing annuity: FV = pmt1 * (CF - savings growth - CF - salary growth)/(i-g) (5) where CF means compounding factor pmt1 is the first payment=$10,500 in Exhibit II, CF-savings growth= (1-i)M, and CF-salary growth= (1+g)M, i=0.06, g=0.05.

With respect to the number of years covered, a suitable formula can be obtained from the equation (4) above: Years covered = ln(n/(n-i))/ln(1+i) (6) This equation provides the number of years as a function of the size of the liquid in the bathtub ($644,281.06 in the Exhibit II) to two rates–the inflow (interest i) at 4% and the outflow (expenses, n) n = pmt/pv = $52,500/$644,281.06 = 8.15%. (Note: n > i). These formulas summarize and highlight the variables at play and the differences between Cases A and B. Case B has more initial liquidity and, while the inflow rate is the same in both cases, the leakage/outflow rate in Case A is almost twice as large as that in Case B. Table 1: Summary information Source: Author’s work.

With respect to the materials on the articles mentioned above. For the first article, the answer is no: it will not be easy at all for parents to be able to catch up if they wait until their kids leave the nest. In the second article, with that household/individual that is planning five years ahead of retirement, the author advises the individual better watch those remodeling expenses, on the basis of the concept, “Better to pay for it now while you’re drawing a salary” (Finch, 2018). V. Lund (2010) and the Literature and Practice of Retirement Planning Lund’s text does not mention the literature on personal finance, and he does not compare his proposals to the advice and recommendations found in household financial planning practice. That is not what he needs to do to manage his life. As a Renaissance man, he finds his own remedies. Therefore, the best way to honor Lund’s courage and self-assuredness would be for me to finish my technical note at this point as succinctly as possible – simply by adding a few sparse comments on the strengths of the material presented and the customary section with concluding remarks. In doing so, I would implicitly be addressing Lund’s audience, who may or may not be interested in the intricacies of academic contributions, alternative planning tools, and the historical evolution of retirement. Reaching a wider audience, however, may work to everyone’s advantage. For example, readers in this wider audience may include policy-makers and academic researchers in economics, finance, or other areas of endeavor and also attract the consideration of financial planning practitioners. It occurs to me that neither academia nor the profession has come to terms with the “counseling” component of the area referred to as “financial counseling and planning.” Given the interdisciplinary nature of retirement planning and Lund’s approach, it is good to keep in mind the difficulties in labeling and identifying the appropriate content to be examined. Lund’s work about extreme early retirement is, in the end, about retirement. He initiates his search for solutions by self-examination, and then sets a framework of lifestyle and personal life-objectives and to-do’s. He computes numerical targets using his sophisticated mathematical education, which we have shown to be identical to the set of formula known as “the time-value of money” in business and financial management courses. But there is no doubt he is responding to what society is offering to him. And this includes an economic system with a retirement component. Therefore, the concept of retirement and its associated processes is my first area of reference. What is referred to as retirement planning will be my second area of reference. Retirement Lund is living within and assessing the retirement system in the Unites States of America. Like other systems in other countries, it offers a public component and a private component. The private component enjoys tax-preferential treatment – that is, allocations to private retirement accounts are not taxed when earned but when the funds are cashed out. Complementary individual retirement accounts and several options to save and invest funds for retirement are offered by the financial system (e.g., mutual funds) and the economy (e.g., real estate). Lund’s plans are designed to accelerate financial independence without having to wait until the statutory retirement age (e.g., 67.5 years old for people born in the 1950s). He also prepares for financing a complicated issue: health care. Manu countries have dual private and public health care systems. In the USA, the main public component is known as Medicare. Coverage starts at 65 years-old. Group insurance through the workplace is the main supplier of health care before retirement. Private insurance can be prohibitively expensive, and hospital costs financially crippling for households. Limitations concerning “pre-existing medical conditions” restrict transferring insurance among carriers. Lund (2010) has a plan to maintain his heath care coverage. But it is critical to keep in mind that in the USA, as I write these lines, many people could not contemplate not being employed by a firm because they would not be able to afford the costs of paying for a private health care plan themselves. The most distinctive characteristic of Lund’s early retirement extreme (ERE) concept is the break from the conventional retirement planning setup. When reading Lund (2010), one could expect to find some implicit or explicit criticism of the specifics of retirement in his country, but no. Lund seems to be motivated only by a search for freedom. However, not to play and pay for the existing system is a very risky proposition. He could be in the public system as a self-employed individual, as an author for example. It is very difficult to ascertain whether individuals may be attracted to Lund’s ERE because they may not like the retirement plan in their country. Assessing the value of a country’s retirement system is complicated. In fact, in simply trying to trace out the history of retirement, one has the feeling of seeing the topic everywhere and nowhere in particular. For example, Spiegel’s masterly “The Growth of Economic Thought” does not contain the word “retirement” in its comprehensive index, but material related to retirement appears in almost every chapter. A very tight account of discussions implicitly or explicitly related to my present retirement concept and policies can be expressed with reference to some well-known authors and areas of inquiry: Grouping 1. The development of government systems, from feudal monarchies to modern republics that include social protection systems. Religious influences as in the doctrines of the Fathers of the Church and medieval economic thought emphasizing charity. Development of professional associations (e.g., guilds) with mechanisms to help their members settle professionally and find shelter and some protection from misfortunes (wars, fires, health, and so on). Grouping 2. Enlightenment concepts such as Rousseau’s social contract, Locke’s research on the relationship between property and liberty, Bentham’s idea of social utility, and Adam Smith focus on advantages provided by a well-functioning economy. Grouping 3. Marx’s labor-based theory of value and social dialectics. Labor movements and communitarian initiatives (e.g., Proudhon’s cooperatives, mutualism, communes, etc.). Jean Baptiste Say’s emphasis on markets and market-provided solutions instead of government initiatives. John Stuart Mill’s unification of Politics and Economics, with discussions of socialism and communism. Schumpeter’s analysis of social value, capitalism, and democracy. Von Mises’s analysis of the interaction between private decision and the economic context. Late 1880s implementation of social-oriented mechanisms using the modern concept of retirement by Chancellor Bismarck. Grouping 4. John Maynard Keynes’s focus on employment and government-led, consumption-strengthening crisis management, to be followed by added socioeconomic policies – e.g., Roosevelt’s New Deal and the enactment of laws like the Social Security Administration (1935). Grouping 5. Development of “economic security” concepts and economic theories advancing and framing the modern approaches to retirement, together with the corresponding tools for retirement planning. The reader interested in the history of modern retirement policies is referred to Spiegel (1991), the presentation available at the Social Security Administration website, Wikipedia’s brief History of Retirement entry, and the Georgetown University Law Center brief on the development of retirement in the USA. The conclusions to be reached are, first, that public retirement systems, together with public health care systems, are major achievements in any civilization and culture. Public education, transportation, and help in securing food, water, and shelter come next. These supports presuppose very hard-to-reach levels of social efficiency and cultural sensitivity. And, second, without a doubt, anyone interested in pursuing Lund’s plans is best advised to secure his/her access to the existing public retirement plan in his/her home country. Retirement Planning Literature and Practice Retirement planning must be studied as a subset of Personal Finance, which is the current umbrella term under which are organized a variety of initiatives with incidence in household financial management over time. The main tributaries to this area are economics, policymaking and the law, and several areas within business management – notably finance, but also accounting and management science/decision-making. The discipline of Household Economics provided an early housing for personal finance courses and materials. Using some grouping and lists will save a considerable amount of space while preserving the richness of the topic.

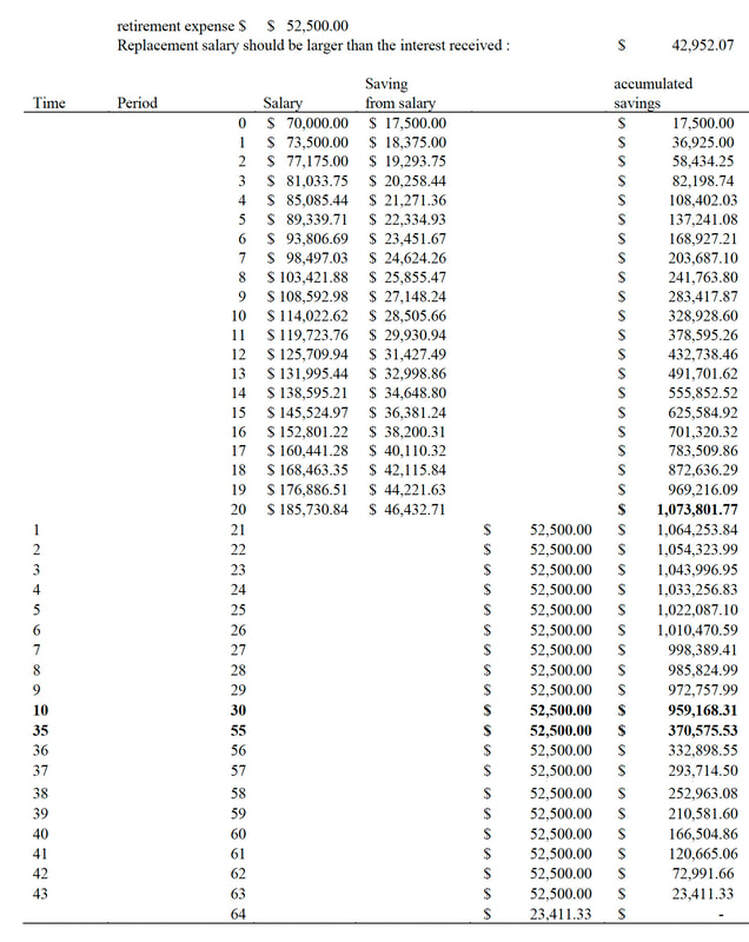

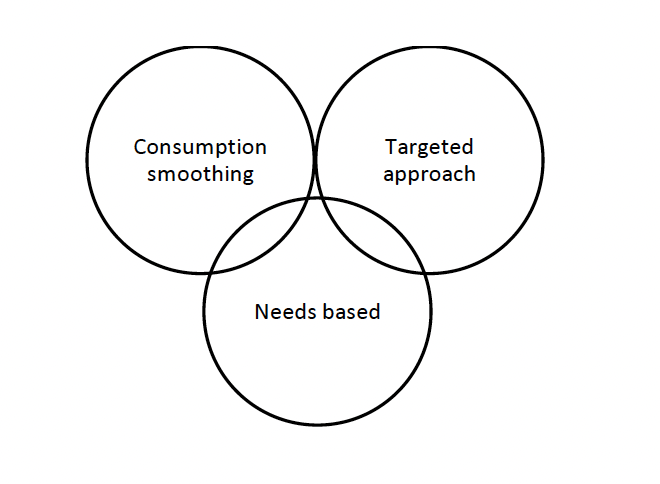

Kotlikoff’s traditional, target-setting approach is exemplified by the following example: A company sets up a retirement fund for an executive, who will retire in 12 years. The fund should finance annual expenses of $43,500 for 20 years, if invested for 12 years earning an annual 6%. The company will fund the fund by investing a yearly sum in an account that provides an 8% rate of return. The calculation process is well known. First, calculate the value of the fund needed at retirement using the present value formula: PV=PMT*ADF (6%, 20) =$43,500*11.4699=$498,941.57. Second, calculate the yearly payment needed to accumulate such value 12 years hence: PMT=FV/ACF=$498,941.57/18.9771=$26,291.7346, where ADF and ACF stand for annuity discounting and annuity compounding facto, respectively. There is some sort of financial beauty in the two-term expression that solves the problem. The accomplishment is not minor, but it is achieved with excessive simplification. What we see in the literature and practice is a far messier approach that runs on the traditional approach but loads it with additional considerations – social security revenues, taxes, changes in revenues, investment allocations and other detail. We can call this approach “needs at retirement plus funding,” or simply “needs-based” for short. We can also refer to Kotlikoff as the “targeted approach,” as it employs targets at each step for the way. This allows us to refer to Kotlikoff’s economist approach as “consumption smoothing.” Figure 1: Consumption smoothin Source: Author’s work.

Note that there is some overlap between “needs based” and “consumption smoothing,” Both classifications still struggle with the complexity of the problem and do not include all financial innovation possibilities in the mix (Bodie, 2002). For this review, I evaluated more than a dozen textbooks contemporary to Lund in both the Personal Finance and Investments categories including the following: Winger and Fraska (1999), Keown (2003), Gitman and Joehnk (2004), Garman and Xiao (1997), Kapoor et alia (2006), Bodie et alia (2008, 2011), Jones (2010), and Gitman and Joehnk (2010). All of them use the “needs at retirement plus investing targets” in their presentations of retirement planning. Kapoor et alia seems like the ideal textbook to accompany Lund (2010). Applied research also makes use of the “needs plus targets approach,” see for example Munell et alia (2011), and consumption smoothing is less used. It is interesting that Excel-based formulations such as Fortin’s (1997) may appear to be close to Lund’s (2010), but upon further inspection, they are not. With respect to practitioners, the Certified Financial Planners Board of Standards (CFP Board, 2021) examination uses the needs-based plus target setting approach, and the examination for the certification materials is close to the traditional approach above (see for example Rattiner, 2007). In sum, retirement planning is not a monolithic practice, and the area is still experiencing its formative years, characterized by considerable dissent, and is still struggling to incorporate certain forms of financial innovation (see Bodie, 2002, and Yeske, 2016). Industry certifications/designations do not help much, and the Financial Industry self-governing policy (FINRA) keeps track of more than 200 of such designations. The “planning” component represents an area in formation, as studied by Yeske (2010; more about this in the next section). After reviewing Lund (2010) in the context of the literature and practice of retirement planning, I can now add further comments to my previous early critique. VI. A Feasible Leap-Forward in Household Financial Planning Practice Lund (2010) makes four contributions to the academic and practitioner literature: 1. Considering and implementing opting out of the existing retirement system. 2. Forward-looking rather than working backwards. 3. Considering goods and services based on their value of use not their price. 4. Focusing on values rather than rates. Lund passes with flying colors Kotlikoff’s muster. Note, for example, how well Lund (2010) reflects one of the main concerns in the consumption-smoothing camp: Traditional financial planning and portfolio management tools tend to focus on the tradeoff between expected returns and risk at a point in time. While these traditional tools provide important investing insights, I demonstrate that a more holistic life-cycle financial planning framework can help form better spending, saving, and investment decisions and reduce living-standard risk through time. Investing and spending are not independent decisions. Spending too aggressively can be as risky, if not far riskier than investing aggressively, in determining one’s future living standard,” (Kotlikoff et alia, 2016, p. 1). Lund’s approach meets a “needs-based approach” in a most meticulously, customized manner, without making the mistake of trying to “keep up with the Joneses” or without reference to anyone, for that matter. In addition, Lund (2010) contains and implements what Yeske (2010) identifies as the categories found in the financial planning literature: quantitative tools, process-orientation, and interior (as in personal, individual preferences-values based) dimension. The ideas and the approach in ERE can help improve retirement planning practice:

Finally, the extended ERE approach prepares for and is well suited to managing some changes taking place:

VII. Concluding Comments I may have lingering thoughts concerning the feasibility of Lund’s early retirement plans and the effects they might have on other people in the household, not to mention about issues related to economic luck, societal pressures, and government’s burdens. Still, there is much to consider in Lund’s brave new world and much that can potentially help us, at the very least, some encouragement to face “the system” and come up with our own answers, in general. It offers encouragement to search, and count, and learn how to do the math, and plan at the specific level. This makes Lund’s text a recommendable, useful contribution to modern, household financial planning. In addition, it could be useful to people with different backgrounds and lifestyles, and might help financial practitioners have more direct and productive conversations with their clients, especially those that need to prepare more seriously. We have seen Lund’s approach is compatible with major financial planning concepts, and it may help in some coming situations (the “gig economy” thing). At some point at the beginning of his book, Lund notes, “Financial independence and extreme early retirement are still for the explorers and the pioneers of a new lifestyle” (p. 8). He not only writes that “it is possible to retire and live on invested savings after just five years of full-time work” (p. 5), but explains how he did so in the Epilogue of the book. For many of us, the escape time may take much longer, but the learning involved is likely to make the wait worth our while. This brings Nietzsche’s prefatory quote to mind – let’s hope we do not wait to get started, and trust we will be able to find our answers and chart our way. After all, we only live once and there are people counting on us. References About The Exam - Certified Financial Planners Board of Standards (CFP Board). (2022). Retrieved from https://www.cfp.net/get-certified/certification-process/exam-requirement/about-the-cfp-exam. Baranzini, M. (2005). Modigliani's life-cycle theory of savings fifty years later. Banca Nazionale del Lavoro Quarterly Review, 58(233-234), 109-172. Berstein, S., & Milza, P. (2009). Histoire de la France au Xxe Siècle - Vol I. 1900-1930. Perrin. Bodie, Z. (2002). Life-cycle Finance in Theory and in Practice. Boston University School of Management Working Paper No. 2002-02. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.313619. Bodie, Z., Kane, A., and Marcus, A. (2008). Essentials of Investments. McGraw Hill Irwin, New York. Bodie, Z., Kane, A., and Marcus, A. (2011). Essentials of Investments. McGraw Hill Irwin, New York. Browning, M., & Crossley, T. F. (2001). The life-cycle model of consumption and saving. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 15(3), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.15.3.3. Campbell, J. (2008). The hero with a thousand faces. New World Library. Novato, California, USA. Chieffe, N., & Rakes, G. (1999). An integrated model for Financial Planning. Financial Services Review, 8(4), 261–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1057-0810(00)00044-5. Dybvig, P. H. (1995). Dusenberry's ratcheting of consumption: Optimal dynamic consumption and investment given intolerance for any decline in standard of living. The Review of Economic Studies. 62(2). 287–313. https://doi.org/10.2307/2297806. Eaglesham, J. (2018). Private Pension Wipes Out Investors. The Wall Street Journal. B1. Fortin, R. (1997). Retirement planning mathematics. Journal of Financial Education, Vo. 23. 73-80. Fuller, A. (2017). What’s my investment fee? A frustrating quest. The Wall Street Journal. R1. Garman, E., and Xiao, J. (1997). The Mathematics of Personal Finance: Using Calculators and Computers. Dame Publications. Houston, Texas. Gitman, L., and Joehnk, L. (2004) Personal Financial Planning. 10th (tenth) Edition Cengage Learning. Boston, Massachusetts, USA. Gitman, L., and Joehnk, L. (2008). Fundamentals of Investing. 10th ed. Pearson Ed. Inc., Boston, MA. Huxley, S, and Tarrazo, M. (2013). Direct Investing in Bonds during Retirement. Journal of Personal Finance.12(1). 99-134. Huxley, S. J., & Burns, J. B. (2005). Asset Dedication: How to Grow Wealthy With the Next Generation of Asset Allocation. McGraw-Hill. New York. Jeffrey, R. (1984). A New Paradigm for Portfolio Risk. The Journal of Portfolio Management. 1(1). 33-40. Jones, C. (2010). Investments: Analysis and Management. Wiley, Hoboken, New Jersey. Kapoor, J., Dlabay, L., and Hughes, J. (2006). Focus on Personal Finance. Mcgraw-Hill/Irwin Series I Finance, Insurance, and Real Estate), New York. Keown, Arthur J. (2004). Personal Finance Update and Workbook Package. 3rd ed. Prentice Hall. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey. Kotlikoff, L. (2007) Economics Approach to Financial Planning. https://kotlikoff.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Economics-Approach-to-Fin-Planning-JFP11-08-07-posted-Jan-3-2008.pdf. Kotlikoff, L. (2019) “Economics Approach to Financial Planning.” Available at: https://kotlikoff.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Economics-Approach-to-Fin-Planning-JFP11-08-07-posted-Jan-3-2008.pdf (Last accessed: April 24, 2022.) Kotlikoff, L., Bergeron, A., Fairfield, W., Mattina, T., and Seychuk, A. (2019) “Rethinking Portfolio Analysis: Living Standard Risk and Reward Over the Life Cycle.” Available at: https://kotlikoff.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Rethinking-Portfolio-Analysis.pdf. Kotlikoff, L., Gokhale, J., and Warshawsky, M. (1999). Comparing the Economic and Conventional Approaches to Financial Planning. National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 7321. Available at: http://www.nber.org/papers/w7321. Lund Fisker, J. (2010). Early Retirement Extreme: A Philosophical and practical guide to financial independence. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 1st edition. Mackintosh, J. (2016). Optimal Portfolio? Why you should buy everything. The Wall Street Journal. C2. Mason. R. (2000). The Social Significance of Consumption: James Duesenberry’s Contribution to Consumer Theory. Journal of Economic Issues 34(3):553-572. Modigliani, F. (1986). Life Cycle, Individual Thrift, and the Wealth of Nations. The American Economic Review. 76(3). 297-313. Munnell, A., Golub-Sass, and Webb, A. (2011). How Much To Save For a Secure Retirement. Center for Retirement Research at Boston College. Number 11-13, 1-11. Available at: https://crr.bc.edu/briefs/how-much-to-save-for-a-secure-retirement/. Nietzsche, F. (1996). The Wanderer and his Shadow. Human, All Too Human. Cambridge University Press. Rattiner, J. (2007). Review for the CFP(R) Certification Examination, Fast Track Study Guide. 1st Edition. Wiley. Hoboken, New Jersey. Schor, J. (1993). The Overworked American: The Unexpected Decline of Leisure. Basic Books. Schor, J. (1999). The Overspent American: Why We Want What We Don’t Need. Harper Perennial. Schor, J. (2010). True Wealth: How and Why Millions of Americans Are Creating a Time-Rich, Ecologically Light, Small Scale, High-Satisfaction Economy. Penguin Books. Smidt, S. (1978). Investment Horizons and Performance Measurement. The Journal of Portfolio Management. 4(2). 18-22. Spiegel, Henry William. (1991). The Growth of Economic Growth. Duke University Press, Durham and London. Tarrazo, M. (2008). A Quantitative Individual Financial Planning Model with Practical Implications. International Journal of Applied Decision Sciences. 1(2). 212-244. Warschauer, T., and Guerin, A. (1987). Optimal Liquidity in Personal Financial Planning. The Financial Review. 22(4). 355-367. Winger, B., and Fraska, R. (1999). Personal Finance . 5th edition. Prentice Hall, New York. Workplace Flexibility. (2010). A Timeline of the Evolution of Retirement in the United States. Memos and Fact Sheets. 50. Georgetown University Law Center. Available at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/legal/50. Yeske, Dave. (2016). A Concise History of the Financial Planning Profession. Journal of Financial Planning. 29(11). 10-13. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2931203. Yeske, David. (2010). Finding the Planning in Financial Planning. The Journal of Financial Planning. 40. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1612507. |